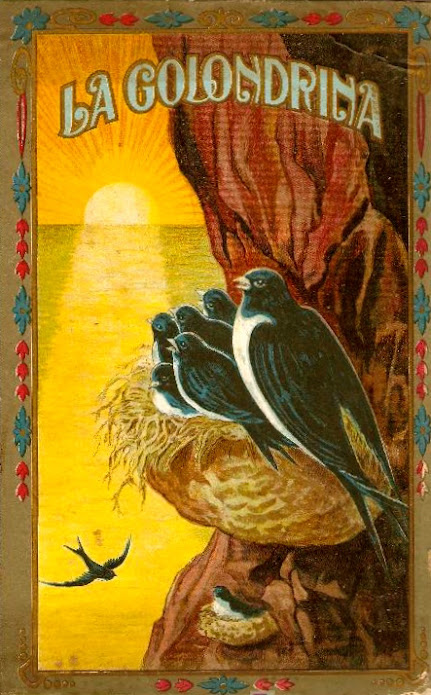

LA GOLONDRINA - A Song that Soars Across Centuries and Crosses Cultures

/by Repstein, THE STRACHWITZ FRONTERA COLLECTION OF MEXICAN AND AMERICAN MEXICAN RECORDINGS, 2019/

*****

During the funeral services of

Mexico’s beloved pop singer José José this month, a tune was played that surely

touched the hearts of most Mexicans, especially those watching from afar. The

song is titled “La Golondrina” (The Swallow), a veritable hymn that for more

than a century has added a note of nostalgia to moments of loss, departure, and

exile.

Ever since Mexico’s war against

French invaders in the mid-1800s, the song has enshrined the image of the

migrating swallow to evoke sentiments of longing for the homeland, most

poignantly for those forced into exile, known as “desterrados,”

literally, “the un-earthed.” But it also has become a cultural means of bidding

farewell on any occasion – a journey, a job retirement, moving away, and of

course, the final farewell for the dearly departed.

The tradition of playing the song as a heartfelt goodbye – or despedida – started virtually from the moment it was conceived in the 19th century by two prominent exiles, a Spaniard and a Mexican, working independently on words and music during separate periods of destierro in Paris.

“La Golondrina” has a long and fascinating history, one where facts are often clouded in myth, folklore, and the poetic license of good storytelling. Tracing the origin story of the song leads us back to pivotal events in world history – the expulsion of the Moors from Spain in the 1500s and the defeat of the French in Mexico three centuries later in the Battle of Cinco de Mayo. More on that convoluted genesis in a moment.

First, a look at the global reach of a lovely song named for a sleek bird that travels far and fast.

Early Recordings

Recordings of “La Golondrina” span more than a century, from the era of Edison cylinders to digital streaming.

“The earliest known recording is probably that made by the U.S. Marine Band in either 1896 or 1897 on a two-minute brown wax cylinder for the Columbia Phonograph Company, cylinder number 407,” according to a blog devoted to a history of the song. The earliest vocal recording, the author asserts, was made in 1898 by Arturo Adamini on Edison cylinder 4234. Adamini, an Italian tenor, later recorded the song as a 7-inch, 78-rpm disc for the Berliner label.

One of the most widely cited early versions on 78 is by Brooklyn-born baritone Emilio de Gogorza, who recorded under various aliases on different labels. His label credits for “La Golondrina” began in 1900 as Sig. Carlos Francisco, released on a 7-inch disc (Victor A-1172), then in 1906 as Señor Francisco on a 10-inch record (Victor 4800), and again in 1913 as Carlos Francisco (Victor 62604-A), all distributed by the Victor Talking Machine Co.

“La Golondrina” has appeared in hundreds of versions since those nascent years of recording technology. From the 78-rpm era alone, the Discography of American Historical Recordings at UC Santa Barbara lists 113 recordings from the late 1890s to the year 1965. The last one on the list is a waltz rendition on the Decca label by "Whoopee" John Wilfhart, a Minnesota polka player.

Other recordings of “La Golondrina” on 78, according to Second Hand Songs, a database of cover versions, were made by the Victor Military Band (1914), Bing Crosby (1928), Xavier Cugat and His Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra (1938), the Boston "Pops" Orchestra with Arthur Fiedler, Conductor (1938), and Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians (1949).

The Frontera Collection has more than two dozen recordings of the tune, about half of them issued on 33-pm discs. Caution: not all entries with the same name are the same song, although the nostalgia still remains. In a few of cases, the listed song was one actually written by Ricardo Palmerín and Luis Rosado Vega, and more commonly called “Golondrinas Yucatecas,” which lyrically portrays the swallow as a metaphor for lost youth.

In the second half of the 20th century, as LPs and 45s replaced the 78, “La Golondrina” kept appearing in the repertoires of artists from myriad genres.

The song of the migrating swallow soon took flight, finding its way into the American pop mainstream. It was recorded so frequently by major U.S. artists, either as an instrumental or with Spanish lyrics, that it became one of those enduring Latin songs considered American standards in the early to mid-1900s, along with “Quizás, Quizás, Quizás” (Perhaps Perhaps Perhaps), “Solamente Una Vez” (You Belong to My Heart), “Malagueña” by Ernesto Lecuona, and “Bésame Mucho,” which was even recorded by The Beatles in 1962.

Currently, there are 1,000 individual recordings of “La Golondrina” listed on AllMusic, ranging from Mantovani to Caetano Veloso. The list also includes Spanish-language or instrumental versions by Nat King Cole, Slim Whitman, Perez Prado, Hank Williams, Gene Autry (The Singing Cowboy), Percy Faith, and The Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra. Not to mention other renditions by less mainstream acts, such as Cousin Fuzzy and His Cousins (1960), The Harmonicats (1962), The Mexicali Brass (1966), and The Nashville String Band (1969). The latter was a trio featuring Homer and Jethro, along with guitarist Chet Atkins, who had recorded his own instrumental version in 1955.

The original song has also been featured in Hollywood movies, most famously in director Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), sung by a chorus during a farewell scene, of course. In the sci-fi cult classic Starship Troopers (1997), the tune is played as a solo serenade (on a rare green acrylic, 5-string electric violin), foreshadowing the death of lead character Isabel "Dizzy" Flores.

Many

younger Americans today, whether they know it or not, will recognize the

Mexican tune, even without having heard the Spanish version. That’s true thanks

to a handful of English translations, the most notable being "She Wears My

Ring," written in 1960 by the Nashville songwriting team of Felice &

Boudleaux Bryant ("Bye Bye Love", "Wake Up Little Susie").

It was first recorded that same year by Jimmy Bell, followed by The

Wanderers (1961), Roy

Orbison (1962), Hank Snow (1965), Solomon

King (1968), and Elvis

Presley (1973), among many others.

The English versions, however, changed the meaning of the lyrics, from nostalgic to romantic, minus the sense of yearning for home from afar. A different translation with a strong sense of loss and longing, “We Love But Once,” was recorded in 1960 by pop crooner Pat Boone, with lyrics by Thomas Mac Gillicuddy and Ray Gilbert.

The translations are not limited to English and Spanish versions. In 1968, for example, it became a No. 1 hit in Germany titled “Du sollst nicht weinen” (Thou Shalt Not Cry), for 13-year-old singer Heintje. Two years later, another child star, 9-year-old Anita Hegerland from Norway, scored a Scandinavian hit in Swedish called “Mitt sommarlov” (My Summer Break).

There are so many versions of “La Golondrina” around the globe that a Serbian blogger named Slobodan Darko has made it his mission to compile as many as he can find, from any country, in any language. The Belgrade-based blogger – whose platform In Dreams hosted the aforementioned page on the song’s history – has been posting his ambitious “La Golondrina” discography since 2011. He’s up to 1,500 recordings, including versions in Dutch, Korean, Indonesian, Croatian, Portuguese, English, French, German, and Icelandic. His latest blog entry from October 6, 2019, features Part 103 of his song compilation, including a 1929 recording by violinist George Lipschultz, on a 10-inch, 78-rpm disc (Columbia W147831).

Then again, some songs transcend language with their emotional vibe.

One blogger quickly picked up on the Mexican tune’s melancholy meaning, despite the language barrier. He posted his thoughts at Village Memorial: The Art of Remembrance, a site designed to help people plan proper tributes for their lost loved ones.

“I first heard ‘Las Golondrinas’ (sic) sung by Pedro Infante when I was looking into traditional Mexican music often played at funerals,” the blogger wrote. “The Mariachi music sounds quite graceful behind Pedro Infante’s vocals. The song has a warmth and comforting quality to it. It may be designed to help the bereaved to let go and accept the loss. Some songs are designed to evoke emotion to help people express their feelings, and ‘Las Golondrinas’ has that quality.”

The Swallow as Symbol

The swift swallow, which can be found on every continent, has long been used as a poetic symbol in several cultures, going back to Roman and Greek mythology. Its sleek image appears in classical Chinese paintings, in Islamic pilgrimages to Mecca, and as bad omens in Japan. Some Christians consider them sacred because they believe swallows removed barbs from Christ’s crown of thorns while on the cross. And for centuries, sailors revered the shore-hugging swallow as a sign that long, dangerous journeys had come to an end, making the swallow tattoo an emblem of hope.

In the U.S., the most widely known reference to the migratory birds is their annual return to Mission San Juan Capistrano in Orange County. The storied phenomenon was the title of a hit song, “When the Swallows Return to Capistrano,” recorded in 1940 by Dinah Shore with Xavier Cugat and His Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra. The Frontera archive contains a Spanish version, “Cuando Vuelven Las Golondrinas a Capistrano,” in a tender rendition by vocalist Marco Rosales, on a Varsity label 78.

Despite such worldwide significance, it would be hard to match the cultural prevalence of the swallow throughout Spain and Latin America.

In Mexico, the 19th century song became so ingrained in popular culture that contemporary composers refer to it for their own farewell tunes. “Que Me Toquen Las Golondrinas,” by prolific Mexican songwriter Tomás Méndez, portrays a heart-broken man who begs a bartender to play the original song because he plans to leave, for no place in particular but “lejos, muy lejos” (far, far away). Notice the plural form, “Las Golondrinas,” which in Mexico has come to be used commonly, though incorrectly, instead of the singular of “the swallow,” as originally written.

In the Frontera database, a search for any song with the word “golondrina” in its title yields 234 recordings, from “Agraciada Golondrina” to “Vuelve Golondrina.”

But it’s not just a popular title in music. La Golondrina is a very common name for Mexican restaurants, starting with the landmark eatery at Olvera Street, billed as the first Mexican restaurant in Los Angeles. The ubiquitous bird is also the name of an Airbnb retreat in Cuernavaca, a tapas bar in Sevilla, an old New Mexico rancho serving as a living history museum near Santa Fe. Add to that a hotel in Playa del Carmen. An apartment complex in San Jose. The world’s largest cave shaft (Cave of Swallows) in San Luis Potosí. A 1968 television movie by famed Spanish director Juan de Orduña. Several notable waterfalls in the mountains of Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, and at the confluence of two rivers in the Mayan jungles of Chiapas. And finally, there’s a boat tour in Barcelona named Las Golondrinas that has been operating since 1888, almost as old as its namesake song.

Origin Story: Unraveling Fact from Fiction

The Internet is replete with websites that purport to document the origin story of “La Golondrina,” whose music and lyrics were written separately at different times by different composers. But the online trail is full of unsubstantiated facts, carelessly repeated over and over. As with other cultural histories on the web, reality is often ignored in favor of a good narrative. Let’s see if we can separate the truth from the myth.

We know for a fact who wrote the music – a Mexican musician named Narciso Serradell. But it’s much more difficult to track the true source of the lyrics.

Narciso Serradell Sevilla was born in Alvarado, Veracruz, on January 25, 1843, to a Catalan father and a Mexican mother. Restless and adventurous as a boy, he twice fled the seminary, where he had undertaken religious studies under pressure from his mother, according to Mexican historian Hugo de Grial.

Eventually, he broke from his family and enrolled in medical school. He took part-time jobs at night, rolling cigars and performing at dances. But he ran short of funds and failed to get his degree in medicine.

In 1862, when he was only 19, Serradell joined the ragtag Mexican army assembled to stop the invading French forces. Although Mexico won a temporary victory at the Battle of Puebla on Cinco de Mayo, Serradell was taken prisoner and exiled to France.

From that point, it’s much more difficult to say with certainty how words and music came together to create “La Golondrina” as we know it. A certain creation mythology can be gleaned from several websites.

The original text, as the prevailing story goes, was allegedly written in Arabic by the 16th century Moorish king Abén Humeya (c. 1545-1569), who led a revolt against the Catholic monarchs of Spain. Humeya, whose Christian name was Fernando de Válor y Córdoba, was an actual historic figure, born in Granada with a noble Islamic lineage traced directly to the prophet Muhammad. But Humeya was considered a Morisco, the group of former Muslims who had undergone forced conversion to Christianity following the fall of Granada, the last Moorish stronghold re-captured by the Catholic monarchy in 1492.

History tells us that Humeya was radicalized by the monarchy’s subsequent crackdown on Islamic culture, outlawing their language, traditional clothing, public baths, and any traces of Islamic religious practices. Moriscos saw it as a betrayal of previous reassurances that their traditions would be protected. So Humeya adopted his Arabic name, Muhammad ibn Umayya, was elected king of Granada, and spearheaded the uprising known as the Morisco Revolt, or the War of the Alpujarras, 1568–71.

In the end, the Spanish Crown was victorious and the Moriscos were dispersed, exiled, or enslaved. This is the tragic moment which is said to have inspired the original poem that would evolve into “La Golondrina.” Humeya, supposedly, wrote the original longing lyrics on the ship taking him into exile, as he watched the coast of his beloved homeland disappear in the distance.

There’s just one problem: The Morisco leader was killed two years before the uprising ended. Depending on the source, Abén Humeya was either felled in battle by an arrow to the chest, strangled to death in a coup engineered by the Turks, or hanged by his own men in his palace in the town of Láujar de Andarax.

In any event, he could not have been on that ship, mournfully writing those nostalgic lyrics as he sailed into exile. Humeya is often described as a brute and a philanderer who kidnapped women to take as wives and concubines. But nowhere is he described as a man of letters.

That description, however, does apply to Francisco de Paula Martínez de la Rosa (1787-1862), a Spanish diplomat, politician, philosophy professor, dramatist, and poet who led a privileged but tumultuous life during the revolutionary Spain of the early 1800s. It was Martínez de la Rosa who provided the link between the medieval Moors and modern Mexicans, but not in the way armchair historians would have us believe.

In 2011, a Spanish blogger wrote authoritatively that Humeya’s lost text was unearthed centuries later by an unnamed French investigator in Marrakesh, the exotic, ancient city in Morocco. It went through various translations, one of which was published in a French magazine that was then used as packing material by an unidentified traveler on an unspecified journey. That version of the poem subsequently, somehow, found its way into the hands of Serradell, who added the music.

“¿Curiosa historia, verdad?” asks the blogger, Manuel Medina.

Yes, very curious story indeed. Too bad it’s probably not true. Unfortunately, these fanciful tales about the song’s meandering history are passed on as gospel, and translated to other languages, as if in a multilingual echo chamber. The same unlikely story is repeated in English on websites such as Wikipedia and Revolvy.

What is true is that Martínez de la Rosa was exiled to Paris in 1823, as a result of his involvement in Spain’s political unrest. There, he was swept up by the French Romantic Movement in literature, led by Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, François-René de Chateaubriand, and others. The Spaniard, who was born in Granada, was so impressed by his French colleagues that he decided to write a play in that style, and do it in French.

Abén Humeya, ou la révolte des Maures sous Philippe II debuted in Paris on July 30, 1830, at the historic Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin. In a preface to an edition published that same year, available on the web at Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, the author explains that he wrote the play in French, then translated it himself to Spanish (Abén Humeya, ó la Rebelión de los Moriscos), although some scholars claim the language order was the other way around. Be that as it may, the work today is considered the first historical drama in Spanish.

Reading the text of the play appears to solve the mystery surrounding the source of what would become the famous song. At the top of Act II, Martínez de la Rosa includes a poem he calls a “Romance Morisco,” which is being sung on stage as his lead character, Abén Humeya, lounges on pillows and listens. The song tells the sad story of an exiled Morisco who laments leaving Granada and never seeing his homeland again.

Al dejar Aben Hamet

por siempre a su amada patria,

a cada paso que da

el rostro vuelve y se para;

mas al perderla de vista,

las lágrimas se le saltan;

y en estos tristes acentos

despídese de Granada:

«A Dios, hermoso vergel,

tierra del cielo envidiada,

donde por dicha nací,

donde morir esperaba;

de tu seno y de mi hogar

mi dura estrella me arranca;

y me condena a vivir

y a morir en tierra extraña.

Obviously, this verse is far from the actual lyrics of “La Golondrina.” But it does contain elements found later in the popular song – nostalgia, sentimentalism, melancholy, and the yearning for a lost homeland.

This poetic theme eventually evolved into the Spanish verse that was put to music by Serradell, who also lived in exile in Paris during roughly the same period. Some say that the poem went through several iterations and translations until arriving at the famous final version by Basque poet, playwright, and historian Juan Niceto Zamacois Urrutia (1820-1885), who emigrated to México as a young man. Authoritative sources, as well as record labels, now generally credit Zamacois as the lyricist.

Juan Niceto Zamacois Urrutia (1820-1885)

Juan Niceto Zamacois Urrutia (1820-1885) In any case, “La Golondrina” makes no reference to Abén Humeya and the Moors, nor any specific person or country. What is left is simply the pure longing felt by someone far from home. Plus, an intriguing puzzle hidden within Zamacois’ verses.

In Spanish, the lyrics of “La Golondrina” constitute an acrostic poem. That is, the first letter of each line spells out a romantic hidden message: “Al Objeto De Mi Amor” (To the Object of my Love).

A dónde irá, veloz y fatigada,

La golondrina que de aquí se va?

Oh, si en el viento se hallara extraviada

Buscando abrigo sin poderlo hallar!

Junto a mi lecho le pondré su nido

En donde pueda la estación pasar.

También yo estoy en la región perdido,

Oh, cielo santo!, y sin poder volar.

Dejé también mi patria idolatrada,

Esa mansión que me miró nacer.

Mi vida es hoy errante y angustiada

Y ya no puedo a mi mansión volver.

Ave querida, amada peregrina,

Mi corazón al tuyo acercaré,

Oiré tu canto, tierna golondrina,

Recordaré mi patria y lloraré.

Medina, the blogger, asserts that the 19th century acrostic “curiously coincides” with Humeya’s dedication at the end of his hypothetical Arabic poem, although that’s another flight of fancy.

Finale of the Song Saga

At this point, once again, accounts diverge on several aspects of the song’s final evolution.

Sources agree Serradell wrote the music in 1862, the year he went into exile in Paris. They disagree, however, on exactly when he wrote it, whether before leaving Mexico or after arriving in Paris. In addition, there’s conflicting versions of how he came across the lyrics to begin with.

According to one version, Serradell composed the melody while still in Mexico, as part of an impromptu competition among friends. In his book of musical biographies, Músicos Mexicanos (México: Editorial DIANA, S.A, 1971), Grial asserts that the composer, who also sang and played various wind instruments, regularly attended informal gatherings of artists known as “tertulias,” where guests played music and recited poetry. At one of these meetings in Mexico City, Serradell brought a copy of the Spanish poem about Abén Humeya.

The beauty of the lyrics immediately sparked a challenge to see who could write the best music for the verses in 24 hours, according to Grial.

The following night, Serradell returned with the melody of “La Golondrina,” and he won hands down. Of course, this account allows for a perfect plot point in the story: When the young Serradell departed for his exile in France, writes Grial, his friends wished him farewell by singing his sad song, newly minted, as he and his fellow prisoners joined in.

The alternate account, as reported in Spanish Wikipedia and elsewhere, holds that Serradell wrote the melody during his time in Paris.

Whether inspired by a spirited competition or by the deep nostalgia of living in exile, Serradell had penned a tune that would take on a life of its own.

By 1865, Serradell was back in Mexico, living in his home state of Veracrúz, directing military bands, organizing new “orquestas típicas,” and teaching music. His favorite student was Rodrigo Barcelata, father of the acclaimed composer Lorenzo Barcelata, who wrote the classic waltz “María Elena” and "El Cascabel."

By the end of the century, Serradell had married and returned to Mexico City, where he continued to teach music. Unfortunately, the global success of his song had not brought him financial security, and he was forced to sell his valuable library of books to support himself in his later years, writes Grial. He passed away at age 67 in 1910, the year the Mexican Revolution broke out.

Exactly 100 years after the composer’s death, critically acclaimed Irish folk band The Chieftains released a version of “La Golondrina” on their album San Patricio, co-produced with American roots guitarist Ry Cooder. Released in 2010, the album was inspired by an Irish battalion of soldiers, the San Patricios, who fought on the side of Mexico during the war with the United States (1846-48). Musically, the album highlights the cultural connections that bind the two countries.

When The Chieftains appeared in

Minneapolis to promote the album, the local newspaper ran a feature about the

band. In the very last paragraph, the writer mentioned the historic tune,

instinctively grasping the universal appeal of a song born in exile that speaks

powerfully to all expatriates, whether Moorish, Mexican, or Celtic, yearning

for home.

/ Agustín Gurza